Religion and Environmentalist Movements in Germany

Guest Post from ISSRNC Member Carrie B. Dohe

Carrie B. Dohe is a research associate in the Department of the Study of Religions at the University of Marburg. In 2017, she received a three-year grant from the German Research Foundation to study religiously motivated environmentalist movements in Germany.

Carrie B. Dohe is a research associate in the Department of the Study of Religions at the University of Marburg. In 2017, she received a three-year grant from the German Research Foundation to study religiously motivated environmentalist movements in Germany.

I am currently researching how concern with climate change and global environmental degradation is changing religions by generating new ethical concerns, holidays, activities and practices. By practices I mean not only what is specifically religious (such as, say, prayer), but also environmentalist practices (such as switching to renewable energy) that are interpreted through a religious lens. Of chief interest to me is the growing interreligious cooperation on environmentalist issues and the non-religious factors that either promote or hinder engagement with environmentalism as a religious concern. These were apparent when I started doing the preliminary research necessary to write the grant proposal. I discovered that no one had yet researched this topic in Germany, which provided me with a niche, and a professor I already had contact with was highly supportive of the project. As my research developed, I analyzed creative projects for energy transformation in both Christianity and Islam, an online Jewish environmental portal, and a workshop on Buddhism and ecology. What I saw is that all religious communities struggle with a lack of resources dedicated to environmentalist concerns. Furthermore, religious communities may face intolerance, either as minority cultures or as promoters of worldviews grown suspect in a secularized society. Furthermore, various religious communities may be unwilling to work with each other due to long-standing conflicts that often have their origin elsewhere on the globe. This interreligious conflict is being exacerbated by a rapid turn to the racist right, in Germany and across Europe, which fans the flames of Islamophobia and xenophobia. My previous work on racial and religious ideologies in the psychological theory of Carl Jung attuned me to such discourses, yet now I am studying them as they unfold in the news and on the streets. Fighting such intolerance is a main priority for many newer religious communities in Germany. Religious communities may either win or lose social capital through their engagement with environmentalist concerns, based on their different statuses in Germany.

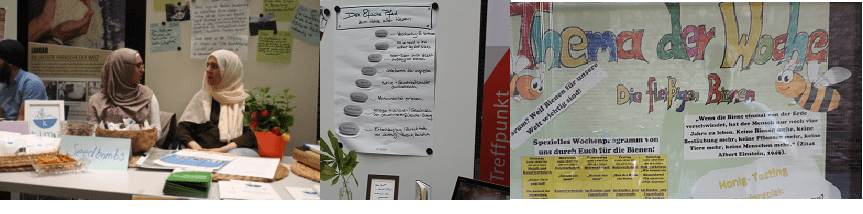

Information tables at the Market of Diversity for environmentalist projects in religious communities: The Sikh Association of Germany (presenting on Eco-Sikh) and Hima e.V.: Environmentalism from an Islamic Perspektive (left) (2) the German Buddhist Union Committee on Buddhism and Environmentalism (center), and Bees for Peace action on April 21, 2018 to build raised beds as feeding sites for bees, Cologne Youth Work Center of the Archbishopric of Cologne (right).

Some of my methods are standard: document analysis, participant observation at conferences and events, and guided interviews. Yet one part of my method may be a bit unusual, in that I decided to initiate an Interreligious Week of Nature Preservation in Cologne and to assume the position of its chief organizer. This Week is part of a larger, interreligious project on “Religions for Biological Diversity” funded by the German Federal Agency of Nature Preservation and directed by the Abrahamic Forum. In the scholarly discussion of religious environmentalism, most studies focus on expressions found within given religions. The “Religions for Biological Diversity” project is a chance to observe how the discourse of religious environmentalism operates in an inter-religious context. During the first Week in Darmstadt in 2017, I played both the insider and the outsider; for 2018, I was fully an outsider to both the Week in Darmstadt and the sponsored Week in Osnabruck. For all three weeks (Cologne, Darmstadt and Osnabruck), I conducted interviews and analyzed both public and internal documents. By assuming such a central role in Cologne, I learned and experienced things that would have eluded me otherwise; through the comparison of the Cologne Week with those in Darmstadt and Osnabruck, I will have a rich mix of material to analyze about the promotion and development of inter-religious religious environmentalism in Germany.

Drawing from a session on environmentalism in the Quran lesson, DITIB Central Mosque, Cologne.

Given that we now live in a new epoch, the Anthropocene, I believe my crossing the borders between insider and outsider is justified. We definitely need more empirical studies to understand whether and to what degree religions are greening, as is often claimed, and my study should contribute to filling in this gap in our knowledge. At the same time, if predictions about a 4-degree rise in the global temperature by century’s end are even partially correct, we need to think outside the disciplinary box. In this light, I offer readers “Bees for Peace,” an incipient interreligious peace network originating during the Interreligious Week of Nature Preservation in Cologne, and featuring feeding sites for bees and other pollinators located at religious communities. Bees are necessary for human well-being, and they cross our self-imposed borders. In both senses, they connect us all. Hence, they can act as peace ambassadors, representing peace, love of the other, and respect for life. You may read more about “Bees for Peace” here.